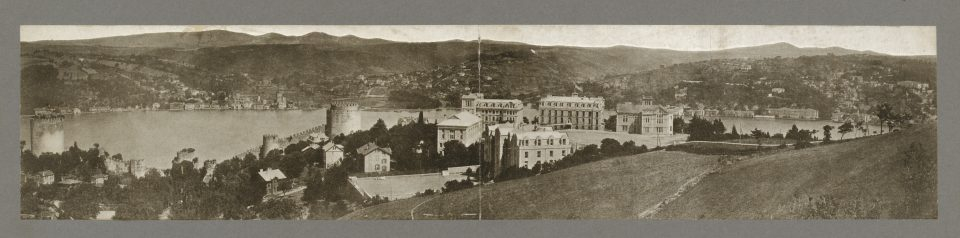

While many architectural historians work in campus settings, and despite the campus being a verdant site for architectural experimentation for architects, campuses have attracted relatively little attention in architectural history writing. Paul Turner argues that the campus is “an American planning tradition”: He explains, “campus sums up the distinctive physical qualities of the American college” (Turner, p. 4). Though it may have originally been intended for the socialization of white American men, Stefan Muthesius shows how the typology became transnational in the post-war educational building boom of the United States, England, Canada, West Germany, and France. Earlier, colleges abroad with missionary roots (Bogazici in Turkey, AUB in Lebanon, AUC in Egypt, Dōshisha University in Japan, EWHA in Korea, Ginling in China, etc) translated the campus typology into non-Western contexts as part of their founders’ attempts to influence local populations, a form of “soft power.” Recent outsourcing of metropolitan universities’ brands in the Global South, in the Gulf States, in Singapore, China, etc., has once again lead to the creation of new campuses as well as heated debates on the implications and impact of such satellite campuses on home bases in North America and Europe.

Spaces of education are examples of Foucault’s “swarming institutions.” Organized education was never intended to “liberate” society. It was always for pragmatic concerns, e.g. for disciplining society, inculcating ideology (e.g. religion, nation states, imperialistic agendas) or maintaining social, racial and class distinction. Today, commercial interests seem to steer the planning and design of knowledge institutions; from the Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao, Spain to new American campuses and museums in the Gulf States or in Singapore (Yale) and China (Liverpool). Whatever their initial motivations may be, contemporary institutions of transcultural learning can never be simply transplants of foreign formal attitudes or vehicles of imposed ideology, or “outposts of empire.” They are also constituted by locally driven change, and, as such, act as independent cultural agents that work transnationally.

What kind of pedagogical models does the design of campuses suggest and promote? How do campuses work as part of larger networks of knowledge institutions? What do we know about the campus typology as it has been translated globally? Crucially at this time of globalization and digital distant learning, are universities developing self-conscious spatial models that align with their pedagogical missions? How does campus design impact architecture and cities beyond the physical limits of the campus?

This research examines the relationship between pedagogy and spatial imagination in campus landscapes.

2 projects :

- Spatializing the Missionary Encounter funded by the SSHRC 2013-2017.

- Building Architectural Networks: American Missionary Schools in the Eastern Mediterranean funded by the FQRSC 2013-2018.

Ipek Tureli, Jean-Pierre Chupin et Carmella Cucuzzella

recherche subventionnée par le Conseil de Recherche en Sciences Humaines du Canada et le Fond Québecois de Recherche en Science Sociales 2013-2018